By: Lorenzo Rivarés

Director of the Center for Selection and Employment at Grupo Eulen, Madrid

Managing personal relationships in the business world has always been a key aspect of human resources management. Some companies forbid their employees from having personal ties to one another, while others refrain from regulating this aspect, saying it is a private matter that concerns the individual as a person more than as an employee; and still others encourage such relationships and take advantage of them to make their processes more efficient. For example, some companies compensate their employees with a referral bonus when they recruit other professionals to work in the company. Employee referral systems, whether compensated or not, have long been popular among companies, and sometimes have results contrary to what are expected.

In an increasingly fast-paced and demanding labor market, the response times required to incorporate workers into a company are increasingly short. These shortened response times oblige firms to use personnel selection systems that are very unlike the scientific method, and frequently involve some variant of the “bring a friend” process. In essence, the “bring a friend” process involves asking a candidate that has already been hired, “do you have any friends we could call who might be good for this job?” Candidates recruit those of their friends they consider to be appropriate to fill the job vacancy and who are interested in the job offered.

Between 1995 and 2009, we worked with Luís González Fernández, full-time professor at the University of Salamanca, to study this recruitment process, conducting empirical research to determine its degree of effectiveness and the reasons for such effectiveness. We carried out our research among temporary employment agencies in Spain, because they allow us to control for workers’ attitudes in the selection process. This is because their work contracts are by nature temporary, and the employees belong to a company different from the one in which they work, so their ties to the company are more transactional (according to the typology defined by Rousseau, 1995, a transactional contract is one with specific terms and a temporary duration) than relational. We wanted to share experiences and propose this investigation among a large number of companies, and worked with the temp agency Flexiplan, one of the largest temporary employment agencies in Spain with more than 9,000 clients a year and more than 45,000 workers in the year 2005. During our work we met with more than 100 client companies interested in our research proposal.

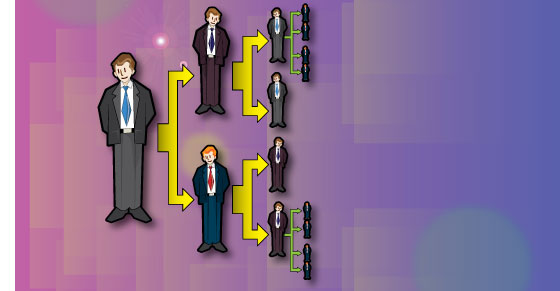

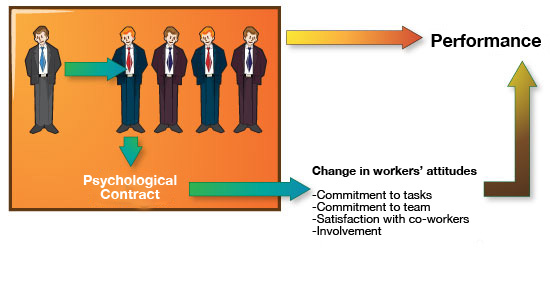

Our hypothesis was that this recruitment process creates a sort of psychological contract, which in turn affects workers’ attitudes, and the attitudes affect their performance. The psychological contract is between the recruiting employee and the friends he or she recruits, and takes the form of a pact that is unofficial but recognized by all the parties: “I am recruiting you because I expect you to do a very good job,” and on the part of each of the recruited workers, “I know you have recruited me because you expect me to do a very good job.” This contract has an affective component, because the parties are friends; a component of expected performance because the whole group expects high performance; and a behavioral component, because the contract is fulfilled by doing a good job. We then hypothesized that the contract would influence the variables “commitment to the job to be performed,” “commitment to the work group,” “job satisfaction,” “satisfaction with co-workers,” and “involvement.” (To determine what attitudes to evaluate in peripheral workers, we took into account the reflection of Morrow, 1993, “clearly peripheral workers can be expected to stress other forms of commitment to their jobs than those who are based in the organization.”) Finally, the whole process would affect workers’ performance (figure 1).

Figure 1: “Bring a Friend” Recruitment Process and relationship to performance

Method

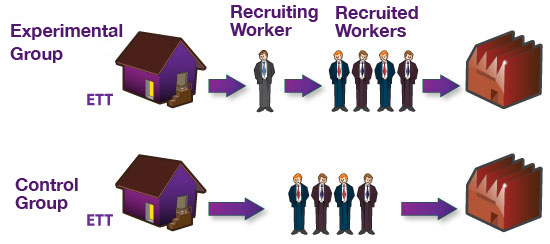

We worked with an experimental design based on equivalent groups, meaning that in each of the groups we compared two exactly equal groups, which differed only in the recruitment system (figure 2). While the experimental group was recruited using the “bring a friend” process, the control group was recruited using the usual temp firm recruitment processes. We compared 11 experimental groups in 6 different companies, for a total of 87 workers studied. We evaluated the level, homogeneity and stability of attitudes through a questionnaire prepared for this purpose, and applied it to each worker at three different points in time: at the start of their labor relationship; one month after hiring; and at the end of their labor relationship, taking into account that all workers had a temporary contract that lasted between three and five months. We prepared 315 records of workers’ attitudes based on their responses to the questionnaire. We analyzed workers’ performance using the dichotomic variable “turnover,” whether provoked by the company (failure to renew the contract or early termination of the contract) or by the worker (voluntary resignation).

Figure 2. Experimental Design of a Study of “Bring a Friend” Recruitment Process in the Temporary Employment Agency industry

Results

The psychological contract was present in all the experimental groups, and in none of the control groups. For the variables “commitment to the team” and “satisfaction with co-workers,” practically all of the comparisons made in the experimental group showed statistically higher scores that were more homogenous and stable over time than the control group. For the “commitment to tasks” and “job satisfaction” variables, most of the experiments with the experimental group showed statistically higher point scores that were more homogenous and stable over time than the control group. In the “involvement” variable, there was very little difference between each pair of groups studied. Among the experimental groups, 6.45% of the subjects belonging to experiments 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 10 and 11 experienced turnover, compared to 33.33% of the subjects in the control groups, permitting us to conclude that the turnover of subjects in the experimental group is significantly lower than that of the control group.

We were greatly surprised to find that in experiments 8 and 9, 100% of the experimental subjects experienced turnover in the first month of the contract, compared to 33% among the control groups. Intrigued by this surprising result, we interviewed the heads of these two experimental groups, and found that in one case the company had decided to dismiss the recruiting worker before the end of the contract, which prompted a negative reaction among the other members of the work team, causing them to resign and/or lower their performance. In the other experiment, the contract for one of the members of the work team was not renewed for medical reasons, also prompting a negative reaction from the other members of the work team.

Conclusions

The “bring a friend” recruitment process generates a perception that a psychological contract has been created between the recruiting worker and the required workers that make up his or her work team, defined in terms of “I am recruiting you because I expect you to do a good job,” and on the part of each of the recruited workers, “you have recruited me because you believe I will do a good job.”

The “bring a friend” recruitment process affects the level, homogeneity and stability of attitudes among short-term workers, very significantly in the variables “commitment to the team” and “satisfaction with co-workers,” somewhat significantly in the variables “commitment to tasks” and “job satisfaction,” but with no impact on the “involvement” variable.

The performance of workers recruited using the “bring a friend” system is markedly group-oriented. A common effect this recruitment system is to significantly increase performance throughout the entire work group; but if the performance is negative, the reaction is also group-wide, making the entire group stand out for its noticeably inferior performance.

For certain temporary hirings, the “bring a friend” recruitment system is very efficient, because it requires few resources–recruit a worker–, the results are immediate, and because it has a very positive impact on worker attitudes and hence their performance. It generates a close-knit group of workers, bound together by the psychological contract among them, and very focused on the success of their performance. If for whatever reason, however–like the dismissal of one of the team members–the attitudes become negative, the reaction extends throughout the group, negatively affecting its performance.

Discussion

Should personal relationships with a company be “managed”? In meetings with more than 100 companies interested in participating in our research, many said that this was a recruitment system they habitually used, but that they did not know how actually efficient it was, and they therefore believed that it required further study. Some of these companies had had some unpleasant experiences in this area, mainly because it generated power networks that ran parallel to the company’s productive organization. Two examples illustrate these experiences: an automotive component factory in the province of Valladolid used this recruitment system to hire most of its workers, but found that it created social networks that were impossible to manage: “we have a bunch of brothers, uncles, nephews and cousins working here, and when the grandmother gets sick they negotiate the personal days they’re going to take, with the threat that if they all take off the same day they would paralyze production.” Another case in point is that of a major multinational Spanish services company that accidentally hired a specialist in theft, who brought his whole gang to work for the company, and they organized among themselves to steal from the company.

Personal relationships within a company are inevitable; workers build a network of relationships because this behavior is inherent to the person; humans are social animals. Certain persons weave these social networks for their own benefit, bringing friends into their work teams, doing changes in favor of an implicit moral debt, praising some workers while discrediting others, according to their own interests. The company’s obligation is to identify and be aware of these practices, to know the risks they entail, and the efficiency of their processes. If social networks arise that run parallel to the company’s productive organizations they will be hard to govern, with private interests that have nothing to do with production, and are even indifferent to the protection of all workers’ rights.

Intentionally or spontaneously, many companies use the “bring a friend” recruitment system in their hiring processes. Understanding and managing the incorporation of workers into companies can help make them more productive, contributing value to the analysis of quantitative results (productivity, turnover, absenteeism …) and making processes like “bring a friend” into efficiency systems. ?

References

Morrow, P. (1993). The Theory and Measurement of Work Commitment. Monographs in Organizational Behaviour and Industrial Relations, volume 15. Jai Press Inc. Greenwich, Connecticut.

Rousseau, D. M. (1995). Psychological contacts in organizations: Understanding written and in written agreements. London, UK: Sage. En Millward, L.J. & Hopkins. L.J. (1998). Psychological Contracts, Organizational and Job Commitment. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 28, 16, 1530-1556

Acerca del Autor

Lorenzo Rivarés Sánchez, es Director del Centro de Selección y Empleo de Grupo Eulen en Madrid. Es Doctor por la Universidad de Salamanca, y posee la Certificación como Profesional en Remuneración Global por la World at Work Society.

12 Comments

Siempre es agradable ver que las teorías que uno se forma con el tiempo son corroboradas por alguien de una manera un poco (bastante) más rigurosa. Muy interesante

Hola Lorenzo,

interesante articulo, con el que estoy totalmente de acuerdo. Me alegro saber de tí.

Un abrazo,

Guillermo

Me ha parecido un artículo especialmente interesante, el trabajo de investigación muy serio

Don Lorenzo:

Brillante explicación y se nota que el trabajo realizado para llegar a las conclusiones finales debe ser completo.

¡Enhorabuena!

La mayoría de los que trabajamos en selección de personal hemos utilizado alguna vez el sistema de reclutamiento bien llamado “tráete un amigo”. Personalmente, hasta ahora lo había utilizado egoístamente a la hora de facilitarme el reclutamiento, obteniendo generalmente buenos resultados sin invertir grandes esfuerzos. Sin lugar a dudas, este artículo me ha servido, no solamente para afianzarme de ser un buen sistema de reclutamiento, sino para ir más allá y tener constancia que además con él posiblemente contribuiría a propiciar aspectos tan relevantes como trabajo en equipo, satisfacción con el trabajo, compromiso con la tarea y en consecuencia, aumento del desempeño a nivel grupal. Felicitaciones por la investigación y gracias por compartirlo.

Hola a todos,conozco el trabajo de Lorenzo Rivarés, trabajamos juntos en el equipo del Centro de Selección y Empleo de Grupo Eulen, Madrid.

Sólo comentar que es un método muy efectivo de reclutamiento ya llevado a la práctica por nosotros en el desempeño técnico, es bien conocido por todos que el “boca en boca” realmente funciona y además si se tiene en cuenta que cualquier trabajador tiene o conoce a alguien cercano en búsqueda activa de empleo las posibilidades se multiplican.

Cuando en una reunión citó el proyecto como trampolín a su Doctorado, me hizo recordar la famosa “venta piramidal” que en algunas empresas dedicadas al “sector ventas” introducieron antaño una cuña en el mercado que sigue dando resultados. Muy distinto es el objetivo “Tráete a un amigo a trabajar” el trabajador: Recluta, perfila, filtra y finalmente resuelve lo que de otra forma, con métodos tradicionales de selección, sólo hacen alargan los procesos.

Totalmente recomendado.

Un saludo, Luís.

Muchos de los que hemos trabajado en trabajo temporal hemos utilizado la frase “no tendrás un amigo que le interese el trabajo”, para solucionarnos el problema que se nos avecinaba si no cubríamos la vacante a tiempo y sin imaginar los efectos positivos que sobre el desempeño del trabajo esa amigo podría aportar…

Excelente trabajo Lorenzo!!!

Muy bueno el artículo, Lorenzo. Enhorabuena.

Un abrazo.

PECO

Comparto con el Sr. Rivarés en la práctica la efectividad de el reclutamiento “Traete un amigo”.

En contratación no sólo temporal sino estable, puedo opinar por mi experiencia en reclutamiento y selección que la base de este tipo de reclutamiento es efectivamente la correcta elección del trabajador-reclutador,

En mi opinión es base para que el equipo de trabajo reclutado tenga un desempeño más eficiente, gracias al contrato psicológico en el que el trabajador que recluta establece las cláusulas que más le interesan a una organización.

Actualmente utilizamos, metódica o esporádicamente, esta forma de reclutamiento en una localidad de alrededor de 20.000 habitantes y tras un periodo cercano a los cinco años de utilización, es una de las razones que contribuyen positivamente a que el clima laboral medido en encuesta anual de clima demuestre tendencias al alza en la mayor parte de los factores.

Una muy buena aportación y estudio teórico de lo que muchos utilizamos en el reclutamiento día a día, de una forma mas o menos consciente.

¿Es el lugar de trabajo un lugar en el que los seres humanos deberían desarrollar al máximo su potencial?

¿Desarrolla un ser humano mejor su potencial rodeado de personas a las que quiere?

¿Necesitamos la ciencia para demostrar lo que el corazón nos dice?

Muy interesante. Gracias y enhorabuena.

Superbly illumainting data here, thanks!