By: Imanol Belausteguigoitia

ITAM

Introducción

In this article, we will review the elements with which organizations can take on an entrepreneurial nature through a three-dimensional model, the Three-dimensional Intrapreneurial Model (TIM). The elements are the following: a) strategy and structure, b) organizational culture and c) formation of intrapreneurs.

It is often difficult for a company to exchange conservative attitudes for more entrepreneurial behaviors, but it can be a highly rewarding venture. Adopting an entrepreneurial culture does not guarantee an organization’s success, and it might even jeopardize it. However, when the environment is taken into account, appropriate strategies are designed and implemented, and personnel are trained with an entrepreneurial attitude, the possibilities for success increase significantly. Bygrave (1997) argues that organizations that cannot change become rigid and die like dinosaurs, unable to evolve. One of the biggest motivations for starting one’s own business is the desire to work freely. Many good employees cannot tolerate the company that hires them, among other reasons, because they feel like they are not given enough autonomy to make decisions. They feel stifled by their bosses and by the company, because they do not feel the climate encourages the expression of their ideas and feelings, and independently of their economic motives, they may decide to quit and start their own businesses.

Organizations are constantly losing valuable people, even if they are well-paid, and they are not clear on what they need to do to hold onto them. The cost of high employee turnover can be tremendous, and an organization has a hard time meeting its goals if it cannot maintain a stable, competent and committed team of employees. Companies of an entrepreneurial nature put these teams together and understand the tremendous importance of ideas being generated among their employees (De Clercq et al., 2005).

Empirical evidence shows that entrepreneurial behavior improves a company’s performance, because it strengthens employees’ willingness to run risks and develop new products, processes and services.

The discipline that studies innovation and the creation of new businesses within existing companies is called intrapreneurship, which is associated with the entrepreneurial spirit of organizations and is derived from the term entrepreneur (which in French means “one who undertakes an enterprise”). Although it may be difficult to pronounce and write in our language, the term intrapreneurship has been gaining traction in the Spanish-speaking business world. In a number of countries, it is recognized that entrepreneurial organizations are able to encourage and respond appropriately to technological innovations, among other things, because they can reduce the negative impact of excessive bureaucracy that may suffocate them.

The Three-Dimensional Intrapreneurial Model

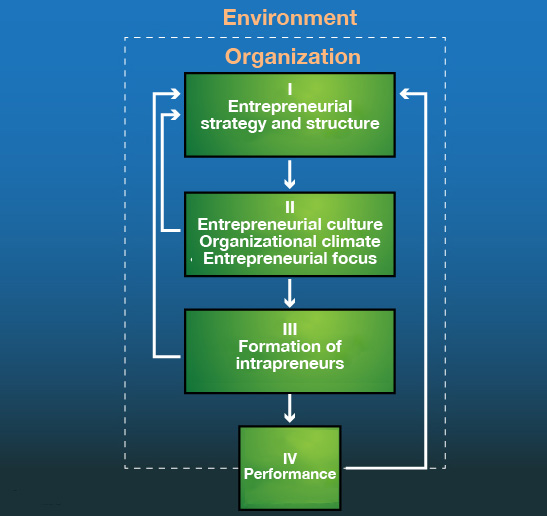

The figure below shows the Three-Dimensional Intrapreneurial Model (TIM), which identifies some factors that influence the willingness of an organization and its employees to take on new challenges.

The following is a simplified scheme of the TIM:

Figure 1. Three-Dimensional Intrapreneurial Model (TIM)

Environment

An environment determines not only the species but also the organizations that will survive. In effect, to endure over time, organizations must have a thorough knowledge of their environment. The environment is made up of a number of factors, like the industry, competition, population, political system, etc. The environment influences design and implementation of strategies (I), culture (II) and the method by which intrapreneurs are formed (III).

I. Entrepreneurial strategy and structure

Designing organizational strategies without considering the nature of the environment is very risky and frequently leads to failure, so proposals must be carefully analyzed. The company must study the industry, determine its nature and ask the basic questions, for example, is it a mature or young industry?

It may be that organizations that intend to become entrepreneurial need to radically change the way they develop or implement strategies, so that they learn to focus on developing new products, systems, services and products. When an organization charts a course that is entrepreneurial in nature, even the people who are reluctant to adopt new paradigms must accept the changes if they want to remain consistent with the organization’s objectives. It is possible to quantitatively define strategic objectives so that all of the employees of the company visualize the changes it desires in a given period of time.

Porter establishes three generic strategies: differentiation, cost leadership and segmentation, in which a series of elements can be specified that make a company more or less entrepreneurial. These strategies lead to quantifiable goals: How many new products? What percentage of sales in total revenues? How many improvement projects? How many gradual or radical process innovations? How many new patents?, among others.

It is not enough to design an strategic plan with an entrepreneurial style; the organization’s very structure must be coherent with the strategic logic. The short-sighted focus and anxiety that comes from doing a job day in and day out in which everything is urgent, can often relegate innovations and entrepreneurial projects to a back seat, because their fruits are often evident only in the medium and long terms. Because of economic pressures, companies innovate and undertake new projects with limited resources, and many times they assign these responsibilities to people already saturated with work, who are unlikely to place a high priority in the new initiatives. This long-term focus often affects immediate results, because it consumes resources, distracts attention and offers no guarantee that the results will to be as expected. Using a sports analogy, the process of innovation is like a team that invests in basic strengths and resists the temptation to rack up a quick streak of wins by hiring proven athletes. It must be patient and wait for the rookies to become a championship team over time.

In conclusion, if organizations really want to their entrepreneurial activity to pay off, even if it means additional investment, they must have the right personnel structure, which frequently means creating new teams of employees.

II. Entrepreneurial culture

Among the characteristic behaviors of an organization that lacks entrepreneurial culture is that it punishes failure and deviations from the plan. Although the results are not as expected and responsibility lies with whoever made the decisions, the punishments are unpredictable, generating fear and paralysis among the workers. In contrast, an organization with an entrepreneurial attitude assumes failures as an inevitable part of the learning curve, another step along the path to reaching their final objective. The TIM model divides entrepreneurial culture into two factors: entrepreneurial focus and organizational climate.

a) Entrepreneurial focus

There is evidence that organizations with an entrepreneurial focus, whose workers function more as entrepreneurs (intrapreneurs) than salaried workers, are more capable of taking risk, innovating and being more proactive. An enterprising organization is one that promotes the pursuit of opportunities, adapting its structure, management and processes to the idea of increasing its versatility, speed and creativity. These companies are welcoming of personal initiatives and decision-making autonomy. They expect that all employees, regardless of where they stand in the hierarchy, seek out solutions and put them into practice. They also inculcate among workers the sense that each one is a leader of their own business, albeit articulated with the rest of their coworkers and aligned with organizational objectives.

The entrepreneurial orientation of an organization can be seen in five factors (Belausteguigoitia and Portillo, 2004, 2004):

- Proactivity. This is an attitude of acting in advance of problems. Members of proactive organizations do not leave things until the end, and instead resolve problems the instant they arise, so they are constantly seeking out opportunities.

- Innovation. This is the capacity to break old paradigms and constantly discover new ways of doing things. Innovation and creativity are inextricably linked.

- Risk. Entrepreneurial organizations assume calculated risks; they are not suicidal, nor do they err on the side of caution, but rather carefully measure the risks of their undertakings. A culture of punishing failure leads an organization’s members to shrink from risk and to lose their entrepreneurial drive.

- Aggressive competitiveness. People and organizations with an entrepreneurial spirit are not easily frightened by competition; in fact, it inspires them to be better. They are not afraid to compete and, like good athletes, they know how to lose, because they take defeat as an important lesson that serves to strengthen them, so that the next time they face their rivals they have a better shot at winning.

- Autonomy. Organizations that are aware that they must foster a climate of freedom among their employees are often entrepreneurial; for this reason, they give them greater authority, responsibility and decision-making power. They avoid excessive bureaucracy as well as a succeeding supervision and control.

b) Organizational climate

There are investigations that have shown that organizational climate is related to the retention and commitment of workers to the organizations (Arias Galicia et al., 2000). The organizational climate can be defined as the properties of the workplace environment that employees perceive as characteristic of their organization, or the way in which people perceive and interpret their surroundings.

Brown and Leigh (1996) refer to the organizational psychological climate, and divide it into two dimensions: psychological security (workers’ perception of a safe environment) and psychological signification (employees’ perception of the meaning of their work). They propose three factors for each dimension.

The factors of psychological security corresponding to the first dimension of organizational psychological climate are the following:

- Support of immediate superior. This is the subordinates’ perception of how they are treated by their boss. There are two extremes in this dimension. At one end there is the inflexible, rigid style that indicates a lack of confidence that the subordinate can do the job without close supervision; on the other, a style that allows methods to be changed in order to take advantage of errors and apply creativity to problem solving.

- Job clarity. This is the degree of precision in the description of job duties and expectations. If the activities of the job and the expectations as to its results are imprecise, tension rises, while satisfaction and commitment diminish (Arias Galicia, 1989; Kahn, 1990).

- Expression of one’s own feelings. This is the workers’ perception of the organizational consequences of expressing their ideas and feelings. If the members of that organization feel confident to communicate their ideas and sentiments, they will have a favorable perception of their workplace environment.

Psychological signification, a profound and to some extent philosophical facet, includes these three factors:

- Personal contribution. This is the workers’ perception about the importance and significance of their job as a means to achieve the organization’s goals. If employees feel that their efforts contribute to the organization’s processes and results, they will perceive that their work is important, and this sentiment can give tremendous significance to the activities they carry out.

- Recognition. This is the conviction that the organization appreciates and values the effort, contributions and results of their workers. One of the most powerful motivations for workers is that their organization recognizes them. Unfortunately, there many employers and bosses who refuse to recognize their subordinates because they believe that it encourages workers to ask for raises that they are not willing to grant (“since I’m doing so well, why aren’t I paid better?”).

- Work as a challenge. This is en employee’s perception about the degree to which the work requires the use of their capacities and abilities. One of the sources of personal development on the job is to face problems and resolve them by applying skills and creativity. If a superior assigns tasks to subordinates and does not allow them to apply their talents, and there is no room for the expression of creativity and ingenuity, the subordinates will interpret their climate as non-stimulating and lacking in significance.

The design of an appropriate organizational climate exercises a positive influence on the workplace environment and on entrepreneurial culture, and also brings other benefits (Belausteguigoitia, 2000).

III. Formation of intrapreneurs

Training workers in the spirit of entrepreneurship must take place at all levels of the organization. It means moving from risk-averse attitudes and the habitual rejection of new paradigms toward an attitude of challenging the status quo and obsessively seeking out new opportunities.

Timmons (2004) makes a distinction between traditional managers and those that function more as entrepreneurs within their organizations. The former possess good management abilities, but they are reluctant to run risks or to innovate. In the case of administrative managers, the difference is obvious: they stick firmly to their budgets and established paradigms and close the door on the development or implementation of new products, systems or processes, because the results cannot be predicted, so by nature they entail uncertainty. Entrepreneurial managers are able not only to accept changes that affect the status quo, but to encourage them. They take on greater risks, and uncertainty is not so uncomfortable for them.

Just as there are traditional or entrepreneurial managers, there are also employees that are more or less entrepreneurial by nature. Each employee will have the possibility of acting as an entrepreneur in their organization. With this, besides contribute to the company, they will gain a sense of freedom.

An organization can benefit from having entrepreneurial employees, but it is not easy to train them to think and act this way.

a) Building leaders

It is indispensable that those who direct others are well-trained to promote the entrepreneurial spirit in their work groups. They must adopt styles of leadership that encourage growth, allow for delegation of responsibility and authority, and draw on all the talents and capacities of their subordinates. Leaders can create the climate needed for intelligent and creative expression by their subordinates, which is necessary for the generation of new ideas.

b) Training employees

Employee training should incorporate both theoretic and practical aspects, meaning both the foundations of entrepreneurial spirit in the organization, and exercises, discussions and workshops aimed at brainstorming and putting new ideas into practice.

c) Job rotation

In recent years, the practice of job rotation has been gaining popularity, because it is believed to promote teamwork and give employees an overall knowledge of the processes within their organizations. It also raises workers’ awareness about the problems faced by their colleagues in other departments, and gives rise to new ideas and problem-solving from different points of view. There are a number of forms of job rotation, which range from a few days to more prolonged periods.

d) Incentives for the intrapreneur

Organizations should reward good performance, innovation and entrepreneurial spirit in order to promote teamwork and encourage creative thinking. These compensation systems, far from inhibiting entrepreneurial decision-making, with all the risks implied, actually encourage it.

IV. Performance

Good performance results from the correct articulation of the three steps that we have just gone over (entrepreneurial strategy and structure, entrepreneurial culture and formation of intrapreneurs). Care must be taken to appropriately define the indicators by which results (performance) will be measured, and not expect that the dissemination of culture, generation of ideas and formation of intrapreneurs to have a short-term impact on the company’s financial statements.

It is fundamental to evaluate the results obtained in order to validate or modify the TIM model. Perhaps some of the phases should be changed to improve the outcome. These processes, in which a later phase feeds back into previous phases, are illustrated in the model with rising arrows (see figure 1).

Conclusions

Organizations that have lost their entrepreneurial spirit sooner or later become rigid, dusty, and perish, because they are overtaken by more dynamic companies. The task of recovering this spirit is a difficult one, but not impossible. The TIM model can be useful not only for organizations that want to regain their entrepreneurial vigor, but also for those who aspire to maintain it.?

References

- Arias Galicia, Mercado, P. y Belausteguigoitia (2000). El compromiso personal hacia la organización, la búsqueda del empleo la intención de permanencia y el esfuerzo. Revista Interamericana de Psicología Ocupacional, (19); 1.

- Belausteguigoitia, I. (2000). La influencia del clima organizacional en el compromiso hacia la organización y el esfuerzo en miembros de empresas familiares mexicanas. Tesis Doctoral. Facultad de Contaduría y Administración. UNAM.

- Belausteguigoitia, I. y Portillo, S. (2004). The family business in Chile and Mexico: organizational climate as antecedent of entrepreneurial orientation. En Entrepreneurship in Latin America, cap. 15. Praeger.

- Brown, S.P. y Leigh T.W. (1996). A new look at psychological climate and its relationships to job involvement, effort and performance. , 81.

- Bygrave, W. (1997). The portable MBA in entrepreneurship, 2a. ed. John Wiley & Sons.

- De Clerq, D., Castañer, X. y Belasteguigoitia, I. (2005). Lobbying for and getting entrepreneurial ideas accepted within an established organization. Frontiers of Entrepreneurial Research. Babson College.

- Timmons, J. (2004). New Venture Creation, 6a ed. McGraw-Hill.

One Comment

HOLA IMANOL

TE FELICITO POR TU PUBLICACION LA CUAL ME PARECE MUY INTERESANTE, ASI MISMO APROVECHO PARA COMENTARTE QUE TUVE EL GUSTO DE SER PARTE LA SEMANA PASADA DEL GRUPO DE LA EMPRESA FINTERRA A LA CUAL LE DISTE UN DIPLOMADO.

EL FIN DE SEMANA VI UNA PELECULA QUE ME PERMITO RECOMENDARTE, IGUAL Y YA LA VISTE, PERO ME PARECIO MUY INTERESANTE Y MUY ADOC A LO QUE NOS COMENTASTE SOBRE LA SUCESION EN LAS EMPRESAS FAMILIARES, LA PELICULA SE LLAMA “MI OTRO YO” O SU TRADUCCION LITERAL “EL CASTOR” CON MEL GIBSON.

SALUDOS Y QUE ESTE MUY BIEN.

One Trackback

[...] http://direccionestrategica.itam.mx/?p=2078 ← Gobierno Corporativo, reto de Pymes [...]