The Functions of the Executive: An Integration of Concepts

Posted By Ceci On 1 December, 2010 @ 10:00 am In Edition 35,Strategy | 47 Comments

By: Carlos Alcérreca

The functions of the executive not only include formulating and implementing strategies, as the field of strategic management seems to suggest. There is a long tradition of studying this concept. The purpose of this paper is to present the main ideas that have historically been discussed on this theme and to try to integrate them.

We will examine here the main perspectives put forward on the functions of executives, with a focus on top management. The 10 main contributions that we will look at are those presented by Fayol (1916), Barnard (1938), Drucker (Lafley, 2009), Quinn (1980), Kotter (1982), Farkas & Wetlaufer (1996), Sull (1999), Garvin (2002), Mintzberg (2003) and Ricart, Llopis & Pastoriza (2007).

Fayol

Fayol was a French mining engineer. In 1916 he published his work Administration industrielle et générale which established management as one of the six functions of a company, in addition to financial, accounting, commercial, technical and security. The responsibilities of management included: prediction, planning, organization, command, coordination and control. Today some people synthesize this process into four functions: planning, organization, direction and control.

Barnard

Barnard was a U.S. business executive who published in 1938 his landmark work: The Functions of the Executive. For Bernard, executives must give priority to three types of functions.

I. Establishing and maintaining a communication system within the organization. Bernard is recognized as having given importance to the handling of the informal organization, which might be called today organizational culture. This function involves:

a. Designing an organizational scheme.

b. Selecting, providing incentives for and control of the executive personnel.

c. Managing the informal organization to obtain the compatibility of the personnel.

II. Securing essential services from its members — in other words, by management — is achieved by:

a. Establishing cooperative relations between members and the organization.

b. Encouraging the services of members through incentives, persuasion, and negotiation.

III. Formulating organizational purposes and objectives — curiously Bernard puts this at the end — involves:

a. Establishing the purpose of the organization.

b. Dividing the purpose into accomplishing concrete objectives and actions.

c. Delegating authority and assigning responsibility to achieve objectives and accomplish stated goals..

Barnard’s theory is very similar to that of Fayol’s, who was also an experienced executive and who came up with the well-known concept of administrative process. Barnard’s plan does not over-emphasize control, but gives great importance to motivation to achieve objectives with effectiveness and efficiency.

Drucker

Peter Drucker desarrolló sus ideas sobre las funciones y responsabilidades del director general (DG) a través del tiempo en múltiples libros. Afortunadamente, un director general de Procter & Gambe, Lafley (2009) las resumió con base en presentaciones orales que Drucker realizó para la empresa.

Para Drucker, las principales funciones de un DG incluyen:

- Defining and interpreting the relevant/significant external environment. Making sense of the environment that surrounds us by defining which elements must be taken into account in decisions.

- Deciding what company has an organizational scheme. Determining which one does not have one and therefore avoiding it.

- Balancing current performance with the required investments for the future. Investing in the future reduces profit in the short term because many investments appear as expenses. For a time, investment results in an increase of assets without an equivalent increase in income, while the product is developed, installations are built and a market is created. On the other hand, profits obtained today are certain while performance expected in the future is always uncertain.

- Shaping values and organizational standards. These are the basic ingredients of an organizational culture that must be channeled in a positive direction.

Drucker emphasizes that the work of the general manager differs from that of other executives in that he/she is the person who mainly can and must “connect the world outside the organization (society, economy, technology, markets and customers) with the world inside the organization. (The general manager) is responsible for understanding, interpreting and disseminating his/her perspective on the environment.”

The general manager has to understand all the groups involved with the company, identifying the interests in conflict and seeing how these may correspond with the capabilities and limitations of the organization. In addition, taking into account that costs are generated only inside the organization while revenue actually comes from outside, the general manager must relate and balance revenues and costs to maintain profitability.

Drucker believes that the general manager is the only one who can see the external and internal environment in a holistic manner. Other executives have biases as a result of their responsibilities: they have a narrower view and look more inward. The general manager sees opportunities others don’t see and makes the tough decisions. He/she is responsible for the overall performance of the organization: its profits, its sustainable growth and the satisfaction of all the groups involved in the organization or stakeholders.

Kotter

John Kotter (1982) is a professor at the Harvard Business School. He conducted an empirical study on the functions of general managers and discovered several patterns in their behavior: They spend most of their time (75%) with other people in addition to superiors and their subordinates; they talk about a wide variety of topics; they ask lots of questions; they rarely seem to make important decisions; they joke a lot and often talk about topics unrelated to their work; the issues they discuss often do not seem to be of importance to the organization; they rarely give orders in the traditional sense; they often try to influence others; they react to the initiatives of others; much of their day is not planned in detail; they spend a large part of their time with others in short and disconnected conversations; and they work many hours (60 a week on average).

Kotter found that general managers have two key roles:

* Setting agendas. Developing agendas for activities with multiple objectives and having the power to implement them.

*Establishing networks of contacts. Included in these network are people above, below and at the same level in the organizational hierarchy. They integrate any person who they can depend on at any given moment. They use direct and indirect influence so that their networks respond to their agendas.

The concept of agenda seems to replace that of strategy within Kotter’s framework, and although it is not clearly defined, it seems to list topics, objectives and actions to be performed, in addition to the specific times in which they will be carried out. The concept of networks as a source of information and mechanism of influence also has grown in recent years. Kotter was among the first authors to use this concept.

Although Kotter’s framework involves only two elements, it has the advantage of focusing on few aspects which are, at the same time, two key elements in executive work.

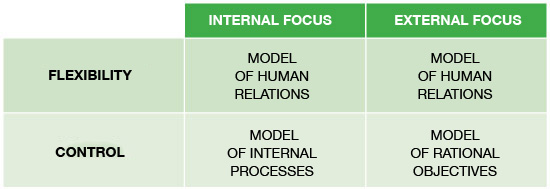

Quinn

Based on a review of the literature published on management, Quinn, a professor at the University of Michigan, uses a conceptual framework called “competing values” to establish four management models for executives. These management models are conceptual frameworks or ways of thinking about the administrative problems facing executives. These models differ to the degree in which they emphasize control versus flexibility, and to the degree in which they address topics that are external or internal to the organization. Each model operates through two executive roles and each one requires multiple skills. These models are:

- Model of rational goals. Emphasis on control and the external perspective.

- Model of internal processes. Emphasis on control and internal perspective.

- Model of human relations. Emphasis on flexibility and internal perspective.

- Model of open systems. Emphasis on flexibility and external perspective.

Table 1. Management Models

I. Model of Rational Objectives. Executives who use this adopt two types of roles: director and producer. Each role requires certain abilities and skills.

Role of director (clarifies expectations, decisive initiator, gives instructions). His/her skills include being able to take initiative, establish goals and the ability to delegate effectively.

Role of producer (oriented to the task and job, high energy, accepts responsibility). This requires abilities such as self-motivation to achieve high personal productivity, motivating others, and time and stress management.

II. Model of Internal Processes. These executives act as monitors and coordinators.

Role of the monitor (informed, they watch to see goals are reached, focus on detail, control and analysis). Involves skills such as receiving and organizing information, assessing data with critical thinking and presenting information effectively.

Role of the coordinator (maintains the structure and flow of the process, is reliable and facilitates the work). Requires skills in planning, organizing and design, and control.

III. Model of Human Relations. These executives act as facilitators and mentors.

Role of the facilitator (stimulates the collective effort, develops cohesion and morale, facilitates group solutions of problems). His/her skills include developing work teams, participatory decision-making, and conflict management.

Role of the mentor (develops personnel through orientation, concern for employees he may have protected). Skills include understanding oneself and others, interpersonal communication and development of subordinates.

IV. Open Systems Model. Includes roles as innovators and negotiators.

Role of the innovator (to facilitate adaptation and change, conceptualizes necessary changes, intuitive, visionary, creative). Involves skills such as knowing how to live with constant change, creative thinking and change management.

Broker/negotiator (maintains external legitimacy and obtains external resources, manages image, appearance and reputation, persuasive, influential, politically astute). Skills include developing and maintaining a power base, negotiating agreements and commitments, and negotiating and selling ideas.

The selection, conscious or unconscious, of a managerial model results in the executive becoming interested in certain topics while giving less importance to others. They face various challenges on the job that include using multiple models and points of view to observe the organizational world, learning how to exercise the roles associated with them, and using skills associated with the four models.

Garvin

Professor Garvin (2002) from the Harvard Business School suggests that the work of the general manager consists of handling six processes: strategic, resource allocation, decision-making, learning, and management and change

Strategic processes include:

- Strategy formulation. The process of developing the strategy.

- Strategic programming. The process of specifying goals, plans and policies in order to put the strategy into operation.

- Strategic deployment. The process of implementing the strategy, to convert plans into reality.

Processes of the allocation of resources:

- Preparation of budgets and operating capital

- Processes of management control

- Decision-making processes

- Formulation of problems

- Development of alternatives

- Selecting the action to take

Learning processes:

- Organizational learning: acquisition of knowledge, interpretation of the information and application of what was learned.

- Knowledge Management: sharing what is learned to give it greater use.

Managerial processes:

- Establish direction: gather information, invent a new vision or business model and transfer the vision to tangible terms such as goals, strategies and resource allocation.

- Negotiation and sales. To achieve the commitment of the people and encourage their effort. Involves altering perceptions and deepening the understanding of the information.

- Monitoring and control. To ensure that the organization performs according to expectations.

Processes of change:

- Identification of the need for changing and designing a new system.

- Alteration of the elements of the system.

- Consolidation, institutionalization and revision.

A general manager must properly manage these processes in order to be successful. It is possible to detect a certain level of repetition or duplication in the various processes described by Garvin.

Mintzberg

Professor Mintzberg (2003) of McGill University began to study the functions of the executives in his doctoral thesis, and reached similar conclusions to those of Kotter. He has developed a classification of executive roles based on whether the person uses their time thinking, handling information, dealing with people or directly in action.

Thinking:

- Conceiving the frame of reference for the organization. This is achieved by defining the purpose of the organization (its mission), establishing a perspective of the organization (values and philosophy) and determining the competitive positioning of the products, services and markets (strategy of the organizational unit).

- Setting the agenda, closest to the programming of activities, indicating specific actions and times.

Information Management:

- Communicating information by disseminating data and analysis.

- Control, which in this scheme involves the design of systems, the development of structures and the imposition of direct orders.

Managing people:

- Leading at the individual, group and organizational level.

- Connecting, which means developing a network of people who can be used to obtain information and influence interest groups.

- Managing performance.

- Dealing within, the work done by the executive when performing tasks related to research, sales, production, etc. in the industry in which he participates.

- Dealing without, negotiate to acquire resources and tasks (for example, advertising) carried on outside of the organization.

Mintzberg suggests that there are various levels that result in different styles of executive work. Those who directly manage performance are actors or doers. Those who direct people are leaders. Those who manage information are administrators. You can also add to this list the level of designer of ideas, carried out by administrative thinkers. The level that the executive prefers determines his style.

Farkas & Wetlaufer

The Farkas & Wetlaufer consultants (1996) conducted empirical research among high-level executives and found they had different approaches to leadership. This is a coherent and explicit style of leadership that includes:

- The areas of corporative policy that receive more attention.

- Classes of people and behaviors that the general manager values in an organization.

- Decisions that the general manager makes personally or delegates.

- How they use their time during the day.

As a result of their research they found five approaches to leadership:

- Strategic approach (18%). The executive sees developing a strategy or business model as his fundamental work.

- Human assets approach (22%). Delegates tasks to people and sees his main work as ensuring that the right people are in the organization and that they are trained and motivated to do their work.

- Style of competence (15%). This is a professional executive who is an expert in a field of great interest to the company and its industry (engineer, doctor, etc.)

- Control Style (30). This is an executive with an interest in information, especially financial, who sees as his main task making sure that people do their work and obtain the planned results.

- Approach to change (15%). This is an executive who thinks he was hired to transform the company, which is why he devotes his efforts to making changes that he sees necessary to achieve that change.

Sull

Professor Sull (1999) studied the commitments made by an organization. These types of commitments can be classified as:

Strategic frameworks. The set of assumptions that determine how the executives see the company. Can be converted into blinders.

- Resources. Soft and hard assets. They are durable, designed for a specific strategy, difficult to buy and sell, can give competitive advantages. The resources can be a burdon.

- Processes. How things are done. Can be converted into routines.

- Relations. The connections to employees, customers, suppliers, distributors and shareholders. Can be converted into shackles.

- Values. The set of shared beliefs that determine the corporate culture. Can be converted into dogmas.

Through the life cycle of the company, commitments are vital:

- When an entrepreneur starts a business, decisions regarding commitments give an identity to the organization by defining what can and cannot be done.

- When the company matures, executives reinforce the identity with new commitments.

- When the company declines, the original identity may be insufficient or counter-productive. The company needs to transform the business with new commitments that may contradict the first ones.

Ricart et al.

The IESE professors, Ricart, Llopis & Pastoriza (2007), reviewed the literature of the team and interviewed a number of executives in Spain. They reached the following conclusions about the priorities of management:

- Creating a future and communicating it. Necessary for establishing the direction of the company.

- Constantly adapting the business model in use. In light of the constant changes in the environment.

- Seeing people as the center of the organization. People are the backbone of management’s performance.

- ntegrating with an institutional strategy, which involves establishing principals and organizational values, defining the institutional purposes and developing a philosophy of operation and performance expectations for the organization.

The framework of Ricart et al. manages to integrate several aspects of the literature in the field.

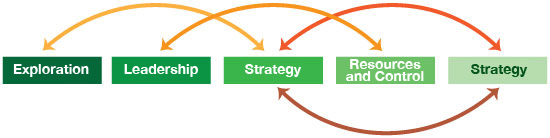

Integrative Framework

I. Exploration

1. Organizational learning. Understanding and developing a framework of the world or the external environment.

2. Developing a network of contacts. Establishing relationships with different audiences or interest groups. External relations. Developing key relations within and between organizations.

II. Leadership

3. Human assets. Recruiting and directing people.

4. Personal leadership. The values, skills, experiences, tactics and personality of those who exercise leadership in the organization.

III. Strategy

5. Setting values and principals.

6. Inventing and creating the future. Vision or image of the future that might exist. Deciding which businesses to work with. Purpose and objectives.

7. Developing and constantly adjusting the business model. Strategic framework.

8. Innovation and change management. Finding new ways to organize and create organizations.

IV. Resources and control

9. Development and exercise of key skills in the organization.

10. Resource management. Investment decisions and performance.

11. Control of information. Establishing expectations and performance evaluation.

V. Operation

12. Developing and maintaining processes and organizational structures. Philosophy of functioning and decision-making. Operative indicators. 13. Preparing and maintaining a schedule of activities. Actions to be taken personally.

Figure 2. The functions of the executive

It is necessary to make decisions about each one of these topics. We can identify at least five management styles according to the emphasis that an executive gives to these activities or themes: explorer, strategist, operator, leader and comptroller.

In a second level of integration we need to think about what will be the relationship between these elements. These can be (Pascale, 1990):

Synchronization and fit between the various elements to increase the synergy.

Fragmentation and autonomous specialization of each element to facilitate their administration. “Live and let live.”

Setting tensions or rivalry between the various elements and managing the resulting conflict. Handling the paradoxes that always result in a complex organization through balancing the opposites.

Moving beyond the dilemmas and finding ways to manage the resulting synthesis. This can be achieved by: changing the level of analysis, altering positions through time, orchestrating a dialectical synthesis to keep the set of tensions simultaneously in dynamic movement, or introduce new concepts to dissolve the paradox.

Organizations need to focus their energies on key topics, but should not be allowed to embrace a theme or area of emphasis and neglect its opposite. An imbalance — an overemphasis — removes healthy tension levels and resistance in organizations. This perspective results in organizations without distinction that do not have creative tension. Too much balance or an excess of consistency may lead to passivity. To maintain organizational vitality, it is necessary to avoid both excessive coherency as well as a lack of focus.

In a third level of integration, we should note that the different authors do not speak exactly about the same thing. The concept that they examine can be functions, management models, roles, processes, approaches to leadership, commitments and priorities of top management. After reviewing the concepts we can say that:

1. The managerial model is a conceptual framework in the minds of executives that results from their education, experiences and the influence of other executives in the organization.

2. Functions are specific tasks performed by executives.

3. Roles are coherent patterns of tasks that have similar criteria of effectiveness.

4. Processes are sequences of tasks that are usually performed by several people.

5. Approaches to leadership style are consistent and explicit, i.e., they are preferences in the roles adopted by an executive that result in certain priorities.

6. The priorities of an executive are preferences with regard to the areas of corporate policy that receive more attention, the people and behaviors that the general manager values in an organization, the decisions the general manager makes personally or delegates, and how he uses his time during the day.

7. Commitments are any action that an executive takes which requires the organization to engage in specific behaviors in the future. Commitments many times take the form of public statements or signing formal documents.

Each management model determines different tasks and roles. Executives adopt approaches to leadership with regard to these roles and set their priorities in relation to persons, activities, decisions, etc. As a result of these activities, commitments are made.

In conclusion, although the authors of the theme, the functions of the executive, do not all speak exactly about the same thing, we can say that their concepts are highly related and therefore reach similar conclusions. The use of different concepts enriches the theory on the subject, giving it different nuances.

References

Barnard, The Functions of the Executive, Norton, 1938.

Farkas & Wetlaufer, The Ways Chief Executive Officers Lead, Harvard Business Review, May-June 1996.

Fayol, H. Administración industrial y general, El Ateneo, 1996.

Garvin, General Management: Processes and Action, Irwin, 2002.

Bartlett, W. & Ghoshal S., The Individualized Corporation, Harper Perennial, 1997.

Kotter, The General Managers, The Free Press, 1982.

Lafley, “What Only the CEO Can Do”, Harvard Business Review, May 2009.

Mintzberg, H. “The Manager’s Job”, en Mintzberg, Lampel, Quinn & Ghoshal, (2003), The Strategy Process. Concepts, Contexts, Cases, Prentice-Hall, 2003.

Mintzberg, Managing, Berret-Koehler Publishers, 2009.

Pascale, R.T. Managing On the Edge: How the Smartest Companies Use Conflict to Stay Ahead, Simon & Schuster, 1990.

Quinn, Faerman, Thompson, McGrath & St. Clair, Becoming a Master Manager: A Competency Framework, Wiley, 4th Ed. 2006.

Quinn, Faerman, Thompson, & McGrath, Becoming a Master Manager: A Competency Framework, Wiley, 1980.

Ricart, J.E., Llopis & Pastoriza. Yo dirijo: La dirección del siglo XXI según sus protagonistas, Ediciones Deusto, 2007.

Sull, “Why good companies go bad”, Harvard Business Review, 1999.

Sull, Revival of the Fittest: Why Good Companies Go Bad and How Great Managers Remake Them, Harvard Business School Press, 2003.

Article printed from Dirección Estratégica: http://direccionestrategica.itam.mx

URL to article: http://direccionestrategica.itam.mx/las-funciones-del-ejecutivo-una-integracion-de-conceptos/

URLs in this post:

[1] Image: http://direccionestrategica.itam.mx/wp-content/uploads/2010/12/articulo-funejec10d.jpeg

[2] Image: http://direccionestrategica.itam.mx/wp-content/uploads/2010/12/articulo-funejec10d2.jpg.pagespeed.ce_.HUv48Svij6.jpeg