Social Network Myths and Realities

Posted By Ceci On 1 September, 2011 @ 1:40 pm In Edition 38,Marketing | 2 Comments

By: Ricardo Medina

The true reach of personal networks, the drivers of effective change, and their implications for your company

¿Are the so-called “social networks” a fad?

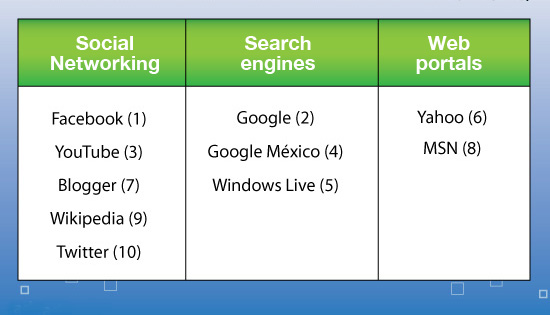

With the mass proliferation of Internet connections, the widespread use of cell phones and the development of online collaboration sites -also known as social networks-, marketing, sales and even politics are facing unprecedented changes. Marketing experts are increasingly interested in the value of social networks. Mexico is no exception to this social shift. The Federal Telecommunications Commission reports that, at the end of 2010, there were 81.3 cell phone lines for every 100 Mexicans. Alexa (2011) found that five of the 10 most popular sites in Mexico provide platforms for online social networks, in which users generate and share their own content. Figure 1 shows this trend in online activities from search engines to social networking.

Figure 1. The ten most popular web sites in Mexico (May 2011)

These changes produce very different results, like the development of smartphone apps, the sudden possibility of re-connecting with old acquaintances, or the democratization of video broadcasting. Interaction between individuals online is growing rapidly, and is at once a tremendous opportunity, a trend in marketing research programs, a threatening reality that some want to control, and a challenge that communication and social sciences professionals must decipher.

To better understand this phenomenon, we must first understand the similarities and differences between online and offline networks, and identify whether the drivers of change are short-lived or long-lasting and, if the latter, what elements are permitting them to permanently alter the way our society works.

The real reach of personal networks

Our first task is to gauge the real impact of personal networks offering peer to peer (p2p) networking. In May 2011, Facebook, the most popular and heavily trafficked social network on the web, had more then 500 million users, with an average of 130 friends each. But these figures do not necessarily mean that everything that happens online will have an impact of that magnitude on the brand, enterprise or reputation of the party that generates it, so we need to differentiate the potential reach from the actual impact.

In their article about online relationship management, the Facebook Data Team (2009a) makes some important points. First of all, they point out the number of “people you know,” which is found through the search toolbar and identified as number of “friends,” represents the total number of people with whom you have connected on Facebook and have decided to identify as acquaintances. This number coincides with the general sociological studies of the number of people an individual will meet during his or her life. But the total amount of bonds that are established in the course someone’s life does not imply a daily relationship.

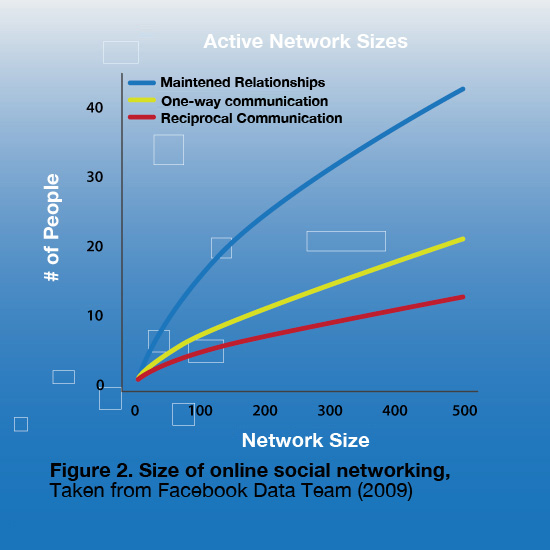

Within the group of acquaintances there is a sub-group of people with whom there is a maintained relationship, and in that sub-group there are smaller sub-groups, first of one-way and then reciprocal communication. In Figure 2, we can see how even the most popular individuals–those with 500 “friends”– actually maintained relationships with forty people and reciprocal communication with only ten individuals. The average person, with 130 people in his network, maintains relationships with only twenty and may converse to four or five people. We can conclude that, in general, the reach of online and off-line personal networks are not substantially different.

Figure 2. Size of online social networking, Taken from Facebook Data Team (2009)

At the same time, the Facebook Data Team (2010) also shows that conversations between individuals on the internet can be charted according to the cluster principle, factoring in the frenetic activity of news in newsfeeds or tweets that spread content to their whole network of acquaintances. People actually engage with friends they get along with, discuss similar topics and communicates with the same symbols. The old saying “birds of a feather flock together” also applies with online relationships.

Engines of change

Although the growth of social networking sites hasn’t made people’s personal networks any larger, or made them more willing to talk to more people about a wider range of subjects, it has revealed three important differences from offline networking: technological support, stability and the speed with which information is spread. These three components have overtaken traditional engagement and, as they reinforce each other, they mark a trend toward social change, with a reach that goes from announcing road closings and the declining service at the restaurant down the street, to the organized mobilization of opposition that demolished Egypt’s governmental regime or supported president Obama’s electoral win in United States.

Today, technological support comes not just from the development of online networking platforms in the Web 2.0, but also from mobility. The rapid proliferation of handheld game consoles, Mp3 players, and smartphones allow for communication and data transmission at unprecedented levels. With this, the Internet has broken free of the anchor of desktop computers: Internet cafés are old hat, and many people who “tweet” don’t even see it as an Internet connection

It also appears that cellphones and online interest groups play a very important role in a youth’s identity and intimacy, so we can safely assume that society will eventually adopt these electronic systems. Rheingold (2002) assures us that the sweeping pace of change in social networking today is a socio-cultural shift as great as the introduction of the printing press, because, among other things, the power of computers has evolved and has gone from making calculations and exchanging files to forming opinions and collective decisions. People don’t just use mobile networks, they express opinions and decide through them. We are going from a means of communication to a mode of social interaction.

It seems that the proliferation of data in response to sharply higher demand will not be a problem either, because it bring an obvious economic benefit to the telecommunications providers and, also, as Intel (2001) reminds us, Moore’s Law establishes that the number of transistors on a chip will double approximately every two years, which increases its efficiency and makes it smaller and cheaper to operate and store.

Stability, on the other hand, means that the p2p networks aren’t just spreading content by word of mouth, but also from text to text and through images. In this way, the durability and impact of our social ties increases significantly. Facebook has been a key vehicle for reviving old ties from the past that have been neglected in more recent times.

In addition, Google and Windows Life systematically organize the proliferation of data from the web, placing automated research within everyone’s grasp. With an infinite amount of data instantly available in text and image form, it’s a lot easier to follow other people’s points of view and take up conversations at any time, as well as to track down other people who have written similar texts.

People’s daily activities and contacts are not the only things readily accessible through the Internet. There are also brands, famous personalities and companies that leave their own trail of messages through self-generated interactions, dialogues with their target groups and in comments on p2p network, even if the famous person himself is not actually involved. Their carefully maintained text-to-text reputation has more grounding, and is less volatile, because it accumulates a history of discussions that can be consulted through any search engine or mobile device. Thus, the margin for error or forgetfulness is smaller every day.

The speed of operation is tied to data mobility and the fact that every individual can record and share content from their cellphone immediately from basically any location, private or public. Now we can also jump between conversations and realities at will: the use of technological communication channels enables us to segment our networks according to the interest of that particular moment, even if we are somewhere else, at a different time. We no longer have to wait until the end of the day or work shift to make room for intimacy, because an SMS that says “I’m thinking about you” is feasible at any moment. Spaces for work and play are intermingled, and in academe it has been acceptable to engage multi-tasking, with resignation for some and enthusiastically for others.

These elements that drive the proliferation and stability of the social networks are apparently an irreversible trend. Although they do not modify the essential structure of personal networks, they require marketing research, communication and other social sciences professionals to assimilate knowledge, interaction strategies and even applications that will allow them to act as fundamental nodes and players in their respective markets and competitive dynamics.

About the author

Ricardo Medina is director of Factor Delta, a consulting firm dedicated to generating and perfecting enterprise growth. He is also a professor in marketing research at ITAM and the author of the book Diferenciarse no basta (Being different is not enough) (Lid Editorial), in which he discusses the creation and design of value proposals. ricardo@factor-delta.com [1]

0738206083

?

References

- Alexa (2011). Top site statistics, , viewed 8 may, 2011.

- Facebook Data Team (2009). Maintained Relationships on Facebook, , consultado el 9 de marzo de 2009.

- Facebook Data Team (2010). What’s on your mind? , consultado el 23 de diciembre de 2010.

- Intel (2001). Moore’s Law, , viewed 12 may, 2011.

- Rheingold, Howard (2002). Multitudes inteligentes, la próxima revolución social. Barcelona: Gedisa.

Article printed from Dirección Estratégica: http://direccionestrategica.itam.mx

URL to article: http://direccionestrategica.itam.mx/desmitificar-las-redes-sociales/

URLs in this post:

[1] ricardo@factor-delta.com: http://direccionestrategica.itam.mxricardo@factor-delta.com