Strategies for Extraordinary Success Every Day

Posted By Ceci On 5 agosto, 2015 @ 12:12 In Contabilidad,Estrategia | No Comments

By: James Ritchie-Dunham

By: James Ritchie-Dunham

We have uncovered tens of thousands of groups experiencing extraordinary success every day. In this article, we highlight what we found about how they achieve and sustain these off-the-charts outcomes, often for decades.

What does this extraordinary success look like? A Texas-based community health center provides services typically only found at top hospitals for a mostly uninsured population, when all other community health centers have been drastically reducing the basic services they provide. A textile mill changed the whole hosiery industry, moving from a focus on pretty foot coverings to preventive foot health products, while paying US-based employees middle-class wages, sustaining a very loyal customer base, while the rest of the industry outsourced its low-cost production to low-wage countries. A global bank’s Latin American back-office operations showed a 10X financial benefit in efficiency gains from fomenting individual potential and respectful relationships within and across teams within a broader outcomes-based business focused predominantly on power through information hording. What is happening in these examples that allows them to realize such unusual outcomes? What are the possibilities and strategies for increasing the incidence of such organizations? What are the implications?

Mainstream, economic resource efficiency-based analysis classifies these groups as outliers, with special resource endowments or situational effects. They are fortunate winners who just happened to show up with the right resources at the right time and place. The community health center’s doctors and nurses were really committed. The sock company’s charismatic founder saw a new niche. The bank operations paid high wages for highly educated leaders. From this perspective, these exciting examples of lucky outliers are interesting but not imitable. We find otherwise. When we used a different analysis, based on the agreements at the foundation of these groups, we found that these seemingly unrelated exemplars share a form of formal and informal agreements that are based in abundance, not scarcity. This distinguishes them from the rest, and this is replicable.

This article’s evidence-based research derives from a validated survey with 2,500 responses from 94 countries and longitudinal field research with 93 of these groups in Belgium, Germany, Guatemala, Mexico, The Netherlands, Romania, South Africa, UK, and the USA, which we have described in a recent book Ecosynomics: The Science of Abundance (Ritchie-Dunham, 2014).

In our work with these extraordinary groups, people were asked to describe their experience of being part of the group. Over and over, in English, German, and Spanish-speaking groups, individuals from the high performing groups used the word “vibrancy” and closely related terms to describe their experience, by which they said they meant a flourishing relationship with a sense of vitality and high energy in contrast to energy-depleting experiences. A typical description was like this one a German leader shared:

“When I am with the people in this effort, I experience a lot more of myself showing up. I learn more about who I am and who I can be. I feel appreciated by everyone, seen for what I uniquely contribute, just as everyone else makes a unique contribution. I love these folks, and we are always seeing new possibilities, what we might achieve from those possibilities, and pathways for developing our capacity to generate those outcomes. It is like creativity is everywhere all of the time, and we are constantly looking for it.”

This contrasts with the description from people in most efforts, like a leader in Guatemala:

“This effort is deadening. I am no better off for having been here. None of my gifts are used here: nobody sees me. I am completely replaceable. Any time I try to share a spark of interest or a new idea, someone stifles it telling me, ‘That’s not the way we do things here.’ No creativity at all, and we only focus on making sure we get the outcomes we were told to get.”

We have heard stories like this in hundreds of groups, where people talk about the experience they have of groups in terms of the energy they have before and after they meeting with the group. They experience their energy depleted in interactions when they leave the group feeling less creative, excited, and engaged. They experience their energy enhanced in interactions when they leave feeling more creative, excited, and engaged. Across cultures as diverse as Mexico, Germany, South Africa, and the USA, these people consistently described five ways they relate to the experience:

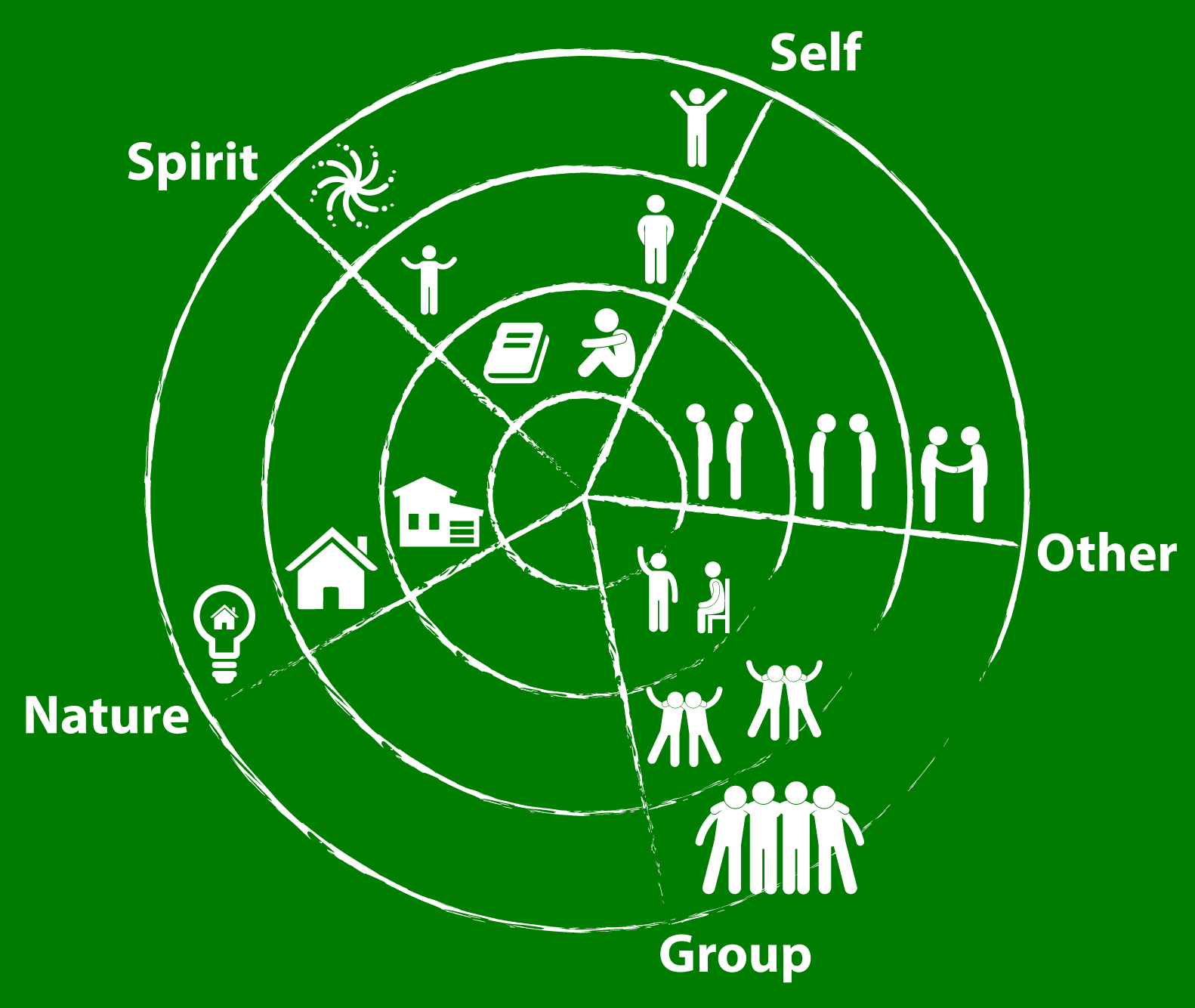

- Self. How much of my own capacities, growth, and potential do I experience when with this group?

- Other. Do I acknowledge and support others and do they support me in being my best and their best?

- Group. Does the group invite each participant to contribute our own unique perspective to the group?

- Nature – the creative process. Does the group focus only on the reality of outcomes and things or also on the reality of learning and developing capacities, relationships, and possibilities?

- Spirit – the creative source. Does the group see only the creative solutions we inherited from our founders or does it look for creativity from experts, or from all of us all of the time?

Our statistical analysis of the 2,500 responses to our survey shows a significant correlation amongst these five relationships, p

The reporting of very similar levels of experience in all five relationships was not expected. The focus of most social-economic theories is on one of the five relationships – they might focus on individual liberty, fairness with the other, group solidarity, nature’s balance, or spiritual transcendence. We find that most groups are designed with organizing principles based on one of these, to the exclusion of the rest (Barkley Rosser & Rosser, 2004; Daly & Farley, 2004; Kornai, 2000; Marx, 1990; Mawd?d?, 2011; Neuberger, 1994; Ritchie-Dunham, 2014; Schumacher, 1973; Smith, 1976). We summarize our findings from the survey and field in Figure 1, representing three concentric rings of similar levels of vibrancy in all five relationships, with the inner ring representing very low vibrancy.

Figure 1. Three Levels of Vibrancy

Starting in 2010, we have tested this survey-based finding in our field research with 93 groups in 9 countries. We find that what differentiates groups is their foundational set of agreements. We define agreements as mutual understandings that guide how they interact. The agreements are the implicit and explicit rules and principles of the game, at the base of their relationships. Sociological research suggests that these implicit, socially embedded rules are based in economic, political, cultural, and social questions (Granovetter, 1985). We can rephrase these four questions into commonsense language:

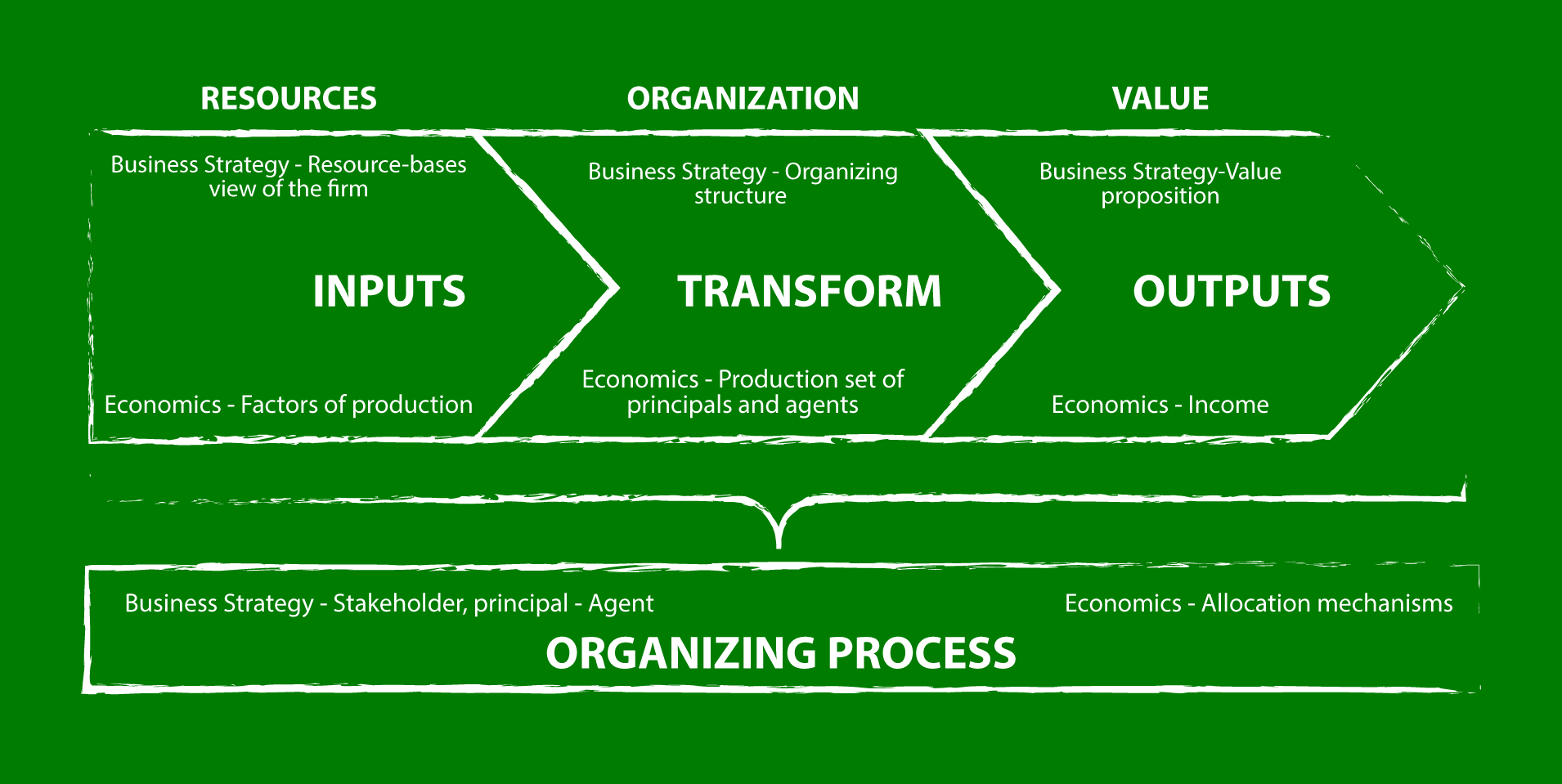

- How much is there? The economic question about the resources available for production and consumption

- Who decides and enforces how to allocate the resources? The political decision mechanism for resource allocation and enforcement

- What criteria are used to decide? The cultural values used to determine how to allocate the resources

- What are the rules of interaction? The social organizing principles, structures and processes

These four questions are often depicted in a linear form, as in Figure 2. The inputs are transformed into outputs of greater value, based on specific organizing principles (Samuelson & Nordhaus, 1995).

Figure 2. Four Areas of Inquiry in Organizational Systems Design

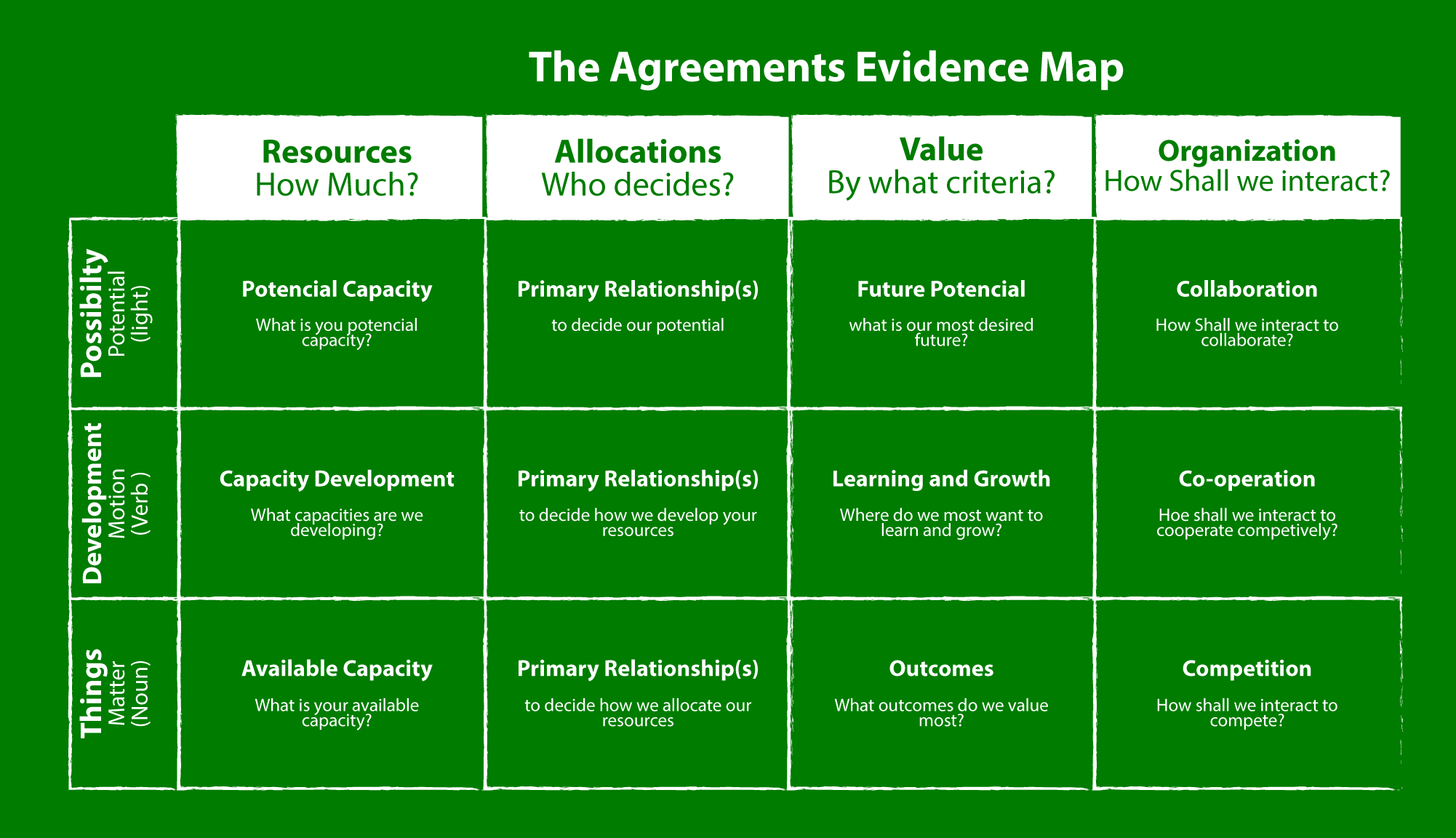

With these four questions, we can now differentiate the three circles in Figure 1, with typical responses from the survey data to each question:

- How much. Responses from the inner-circle experience in Figure 1 describe resources such as the specific capacities people have, amount of existing inventory, and the outcomes already achieved. In experiences describing the middle circle of vibrancy, they see the same resources as the inner-circle groups and the development of new capacities and cooperative relationships, learning along the way. In the outer circle of vibrancy, people add the potential they see in the self, other, group, nature, and spirit. In summary, when we ask people economic resource questions about “how much they see,” the greater the vibrancy they experience, the more they see resources of outcomes, and development, and potential.

- Who decides. Responses from the inner-circle experience make resource allocation decisions using one of the five relationships: decisions are made by individuals or as pairs or as a group or by outcomes (nature) or by the book (spirit). In middle-circle experiences, decision making explicitly included two or three of the relationships, such as freedom to develop one’s own learning and relationship-building process (self), while mentoring others to do the same (other). In the outer circle experience, people describe decision making incorporating all five relationships, where everyone contributes their unique perspectives (group), developing their individual potential (self), and supporting each other (other) through creative processes (spirit) that developed pathways for developing the possibilities the group could see into specific outcomes (nature).

- By what criteria. The experience in the inner circle shows values based in observable outcomes, with decision making in one primary relationship. This might be the amount of available resources, such as money or raw materials for the group. In the middle-circle experience, people describe values around learning, the development of new capacities and the building of relationships, while delivering specific outcomes. In the outer-circle experience, people value the potential they can see in each of the five relationships (in me, in you, in us, in our process, and in the creative potential we manifest), as well as in the development of new capacities and relationships, and the simultaneous achievement of specific outcomes.

- The rules of interaction. The experience in the inner-circle highlights interactions based in the competition for scarce resources: those available right now. In the middle-circle experience, people interact cooperatively with others, sharing resources and connections, working relatively independent of each other. In the outer-circle experience, we see collaborative interactions founded on an explicitly shared higher purpose that celebrates and designs for the value of a diverse set of perspectives integrated to see new possibilities together, increasing individual and collective commitment to the manifestation of these possibility, and agreement of how to and work on them together.

Table 1. The Agreements Evidence Map

This framework produces a different way to think about what drives extraordinary success. The ecosynomics Agreements Evidence Map framework presents a holistic and comprehensive perspective with the five types of relationships. Its distinctive power is that it connects organizational success to the concept of agreements, which thereby provides a focus for organizational leaders and researchers. Moreover, it provides a framework for this investigation that approaches organizational success in terms of interwoven social, economic, political, and cultural challenges.

What would happen if people were to choose agreements for each of the four questions separately, and not simply accept embedded assumptions? What if people want the organizing principle to be fairness, instead of operational efficiency? Focused on generating value for multiple stakeholders, instead of just shareholders? What implicit assumptions about inputs, transformation, outputs, and allocation mechanism are required? This is the problem of socially embedded, implicit assumptions; they are hard to see. Being hard to see seems to influence whether people believe they have a choice or not.

The high-performing practices are based on completely different answers to the four areas of inquiry. The low vibrancy groups answered the how much question with scarcity, while the high vibrancy groups saw abundance when asked this economic question. The groups also gave very different answers for who decides and enforces (the political question), the criteria used (cultural), and the forms of interaction put into place (social). The agreements found in each group changed drastically based on the responses to these four questions.

This inquiry leads to the insight that one’s experience is influenced by the agreements one accepts in how the people in the group relate to each other, and these agreements lead to significantly different outcomes.

The challenge most people seem to face is that the agreements they accept are hard to see: the agreements are embedded in a group’s fundamental assumptions and practices, in the spoken and unspoken rules of the game (Granovetter, 1985; Scott-Morgan, 1994). However, this focus on agreements as the basis for five types of relationships that collectively present a comprehensive description of our human experience, provides a promising center of attention for strategic efforts aimed at sustaining extraordinary success.

Bibliography

Barkley Rosser, Jr., John, & Rosser, Marina V. (2004). Comparative economics in a transforming world economy (Second ed.). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Chaney Jones, Sheri, & Ritchie-Dunham, James L. (2015, May 22). Relational abundance survey results and findings — as of may 11, 2015. Retrieved from jimritchiedunham.wordpress.com/2015/05/11/relational-abundance-survey-results-and-findings/ [1]

Daly, Heman E., & Farley, Joshua. (2004). Ecological economics: Principles and applications. Washington, D.C.: Island Press.

Dawkins, Richard. (2006). The selfish gene: –with a new introduction by the author.

Granovetter, Mark. (1985). Economic action and social structure: The problem of embeddedness. American Journal of Sociology, 91(3), 481-510.

Kornai, Janos. (2000). The socialist system: The political economy of communism. New York: Oxford University Press.

Marx, Karl. (1990). Capital. New York: Penguin Classics.

Mawd?d?, Sayyid Abul A`l?. (2011). First principles of islamic economics. Leicestershire, UK: The Islamic Foundation.

Neuberger, Egon. (1994). Comparing economic systems. In M. Bornstein (Ed.), Comparative economic systems: Models and cases (pp. 20-42). Burr Ridge, Ill: Irwin.

Ritchie-Dunham, James L. . (2014). Ecosynomics: The science of abundance. Amherst, MA, USA: Vibrancy Publishing (ecosynomics.com).

Samuelson, Paul A., & Nordhaus, William D. (1995). Economics (Fifteenth ed.). Boston: Irwin McGraw-Hill.

Schumacher, E.F. (1973). Small is beautiful: Economics as if people mattered. New York: Harper & Row.

Scott-Morgan, Peter. (1994). Unwritten rules of the game. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Smith, Adam. (1976). An inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Article printed from Dirección Estratégica: http://direccionestrategica.itam.mx/ES

URL to article: http://direccionestrategica.itam.mx/ES/strategies-for-extraordinary-success-every-day/

URLs in this post:

[1] jimritchiedunham.wordpress.com/2015/05/11/relational-abundance-survey-results-and-findings/: https://jimritchiedunham.wordpress.com/2015/05/11/relational-abundance-survey-results-and-findings/